Let’s Talk About Executive Privilege

Executive privilege is a legal principle that allows the Executive Branch to deny requests for information made by the Judicial or Legislative Branches, typically in the form of subpoenas. The point of executive privilege is to protect the private nature of candid discussions between the president and his advisors and to protect the internal discussions among Executive Branch officials in general, without having to worry about public scrutiny. Although the concept is not codified (expressly created by statute) it was utilized and developed by past presidents and later established in the Supreme Court Ruling in U.S. v. Nixon, which determined the privilege itself but limited it for prosecutorial necessity, based on the doctrine of Separation of Powers.

How has executive privilege been used in the past?

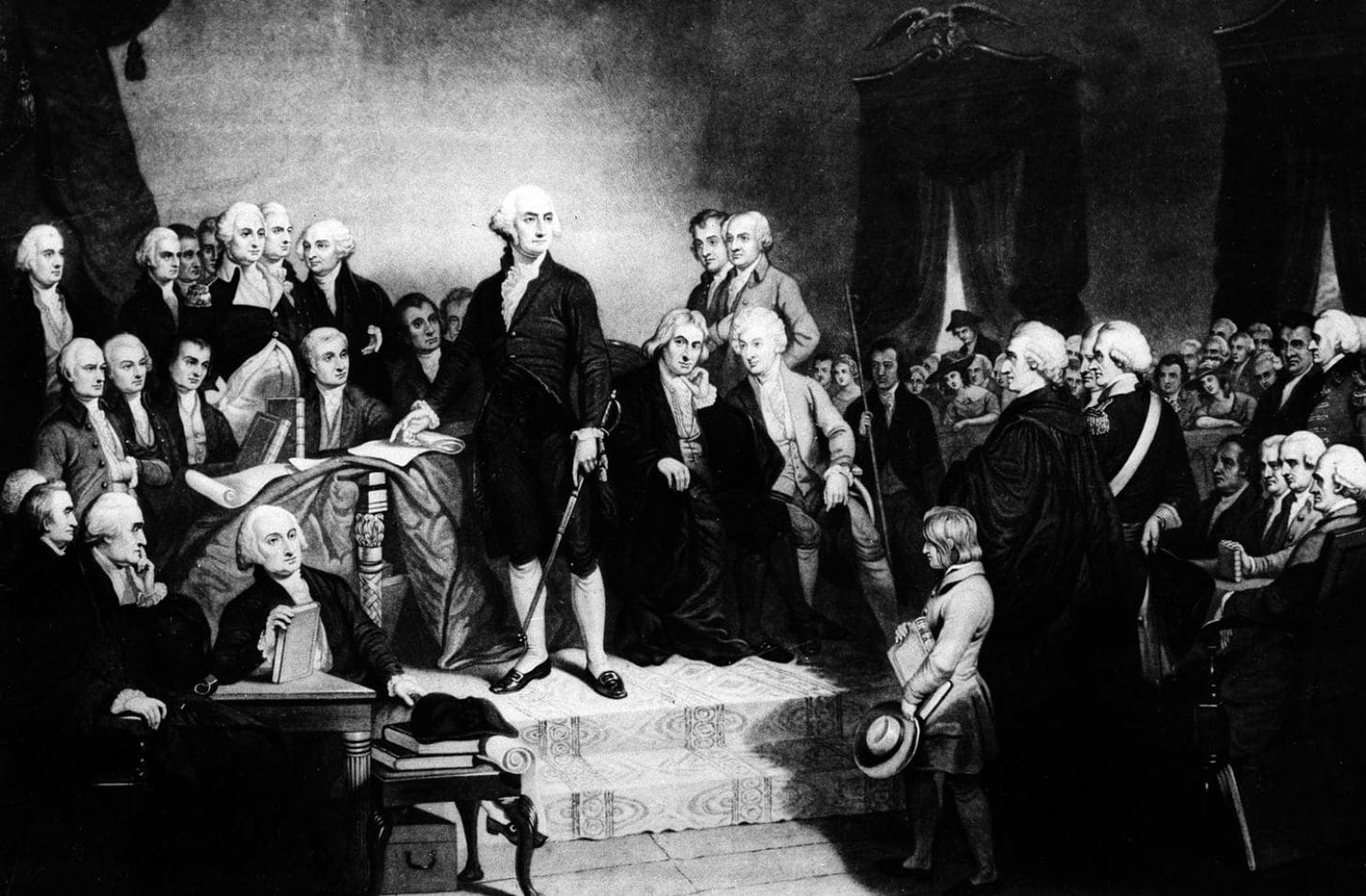

George Washington established executive privilege (even though it wasn’t called that for many years) when Congress asked for records and testimony from a failed military campaign. Washington decided that he had the ability to refuse these requests from Congress on the basis of national security to safeguard the flow of information within the Executive. Washington also tried to withhold the details of a treaty later on for the same reasons and ultimately gave in on both cases in the end, but the standard and subsequent authority of the President to cite privilege to deny Congressional requests was set.

Eisenhower actually coined the term “executive privilege” and was considered to have used it excessively. He saw it as a way to protect confidential information from being made public and to ensure that his advisors and staff could speak and act freely and keep confidences without being concerned about subpoenas. It was thought that because Eisenhower used privilege so often, Presidents who followed were very conscious of it and used it sparingly. So a name added formality, but not everyone agreed on how often it should be invoked and a tradition of easing up on the power after a previous president used it excessively was established.

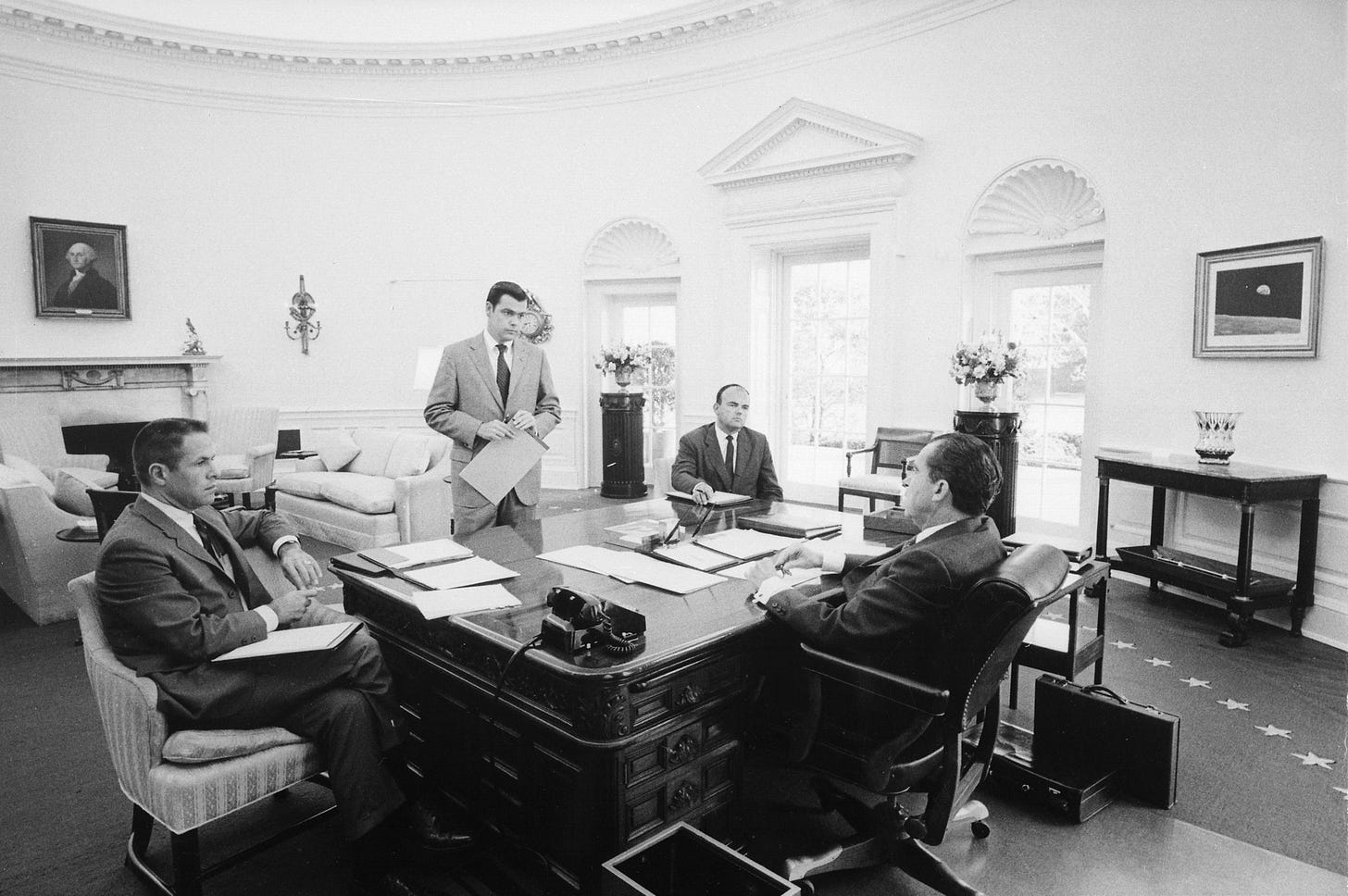

Nixon’s use of executive privilege forever changed how the concept was viewed because he attempted to use it to protect himself and his advisors during the Watergate investigation, which was a shift away from a defense of the public interest. At this point, the courts intervened for the first time in U.S. v. Nixon and the Supreme Court unanimously found that executive privilege is constitutional and can be necessary for national security, but that it’s not all-encompassing. It is best supported in military or diplomatic areas, but the privilege itself is still always limited in favor of the need for “the fundamental demands of due process of law and the fair administration of justice.” There is no absolute, unqualified executive privilege. Essentially, if requested documents are essential to a prosecutorial endeavor, then they must be released and executive privilege does not apply. As a result, the Watergate tapes were turned over to the special prosecutor and Nixon resigned.

Clinton claimed executive privilege several times during his tenure and was challenged in federal court where the court determined the needs to the prosecutor to conduct a full investigation outweighed the confidentiality expected by the Executive Branch. Obama also invoked executive privilege to protect documents and his claim of executive privilege was also rejected by a federal court, and ultimately the subpoenaed documents were all turned over.

Although these are just some examples of presidents invoking executive privilege, these instances reflect the typical understanding of how it is used and the court’s willingness to over-ride presidential authority when an investigation is involved.

What will happen now?

Trump’s recent claim of executive privilege through Attorney General Barr is problematic for many reasons. Privilege was seemingly invoked as a response to the continued Congressional investigation and questioning of William Barr in general, rather than specifically citing which information within the Mueller Report qualified for protection and why. The lack of specificity over which information and why this information was withheld will not help the Trump Administration in court.

The next step will be to take the issue to the courts, where a determination will be made about the legitimacy of Trump’s executive privilege claim.

Additionally, conversations described by witnesses in Mueller’s investigation and related documents don’t fall under the protection of executive privilege because those interviewed spoke with Mueller willingly and the information has already been recorded. Had Trump intended to invoke executive privilege with regard to the witnesses being interviewed or the content resulting from the interviews, he would have needed to do it sooner. Much like attorney-client privilege, executive privilege exists to protect correspondence and conversations. Once a third party, like Mueller or a member of the Special Counsel is told about these conversations, the information is no longer privileged.

There is an argument to be made that the act of making a witness available for interview is not in itself a total waiver of executive privilege and that Trump could still invoke the doctrine, but then the question of why he would wait so long to do it after the release of the Mueller Report is still at issue.

The next step will be to take the issue to the courts, where a determination will be made about the legitimacy of Trump’s executive privilege claim. Then there is the likelihood of appeal and the case ultimately going before the Supreme Court. Due to the recent shift in Justices sitting on the court, there is no doubt that Trump thinks the odds are in his favor. However, years of precedent have established that the limitations of executive privilege are clear and persuasive and the likelihood of him prevailing on his executive privilege claim in the end are quite low. Depending on the final court ruling, documents will either be turned over as requested by Congress, in their un-redacted form or executive privilege will be upheld and certain portions of Mueller’s report will stay redacted.

Now we wait.

Amee Vanderpool writes the “Shero and a Scholar” Newsletter and is an an attorney, contributor to Playboy Magazine, analyst for BBC radio and Director of The Inanna Project. She can be reached at avanderpool@gmail.com or follow her on Twitter @girlsreallyrule.